How time flies: only a year ago, we were in the throes of the biggest global crisis since the Great Depression. As the extent of the damage to institutions in financial centers became evident—starkly highlighted by the Lehman bankruptcy—and the crisis started to affect emerging market economies (EMs), a timely and coordinated countercyclical response was launched.

This helped stave off the worst of the crisis. The IMF supported the global response by increasing its resources and overhauling its lending framework to help those facing financing pressures. A recovery is now taking hold in many parts of the world.

Six months ago, we took a preliminary look at the design and performance of IMF-supported programs in emerging markets. In a forthcoming paper, we are casting a wider net—examining factors that determined the extent to which a broader group of EMs were affected by the crisis, the policy measures they have taken, factors shaping the ongoing recovery, and sustainability considerations over the medium term.

In a nutshell, we find that countries that improved their policy fundamentals and reduced their vulnerabilities in the pre-crisis period generally came out ahead during the crisis: they experienced smaller growth collapses, had more “space” to take countercyclical policy measures, and are recovering faster from the crisis. I describe below our results in more detail.

Impact

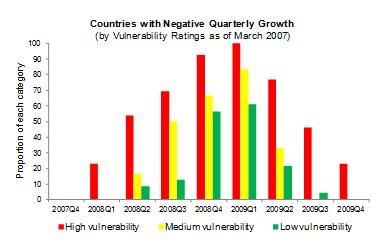

The initial impact of the crisis—whether measured in terms of output contraction or widening of sovereign spreads—was, as expected, more pronounced in EMs that were more integrated with the global economy through trade and capital flows. However, accounting for these linkages, the impact was less intense in countries with better pre-crisis fundamentals and lower external vulnerability indicators.

Holding more reserves helped, but only up to a point. Emerging markets with greater pre-crisis holdings of international reserves relative to external financing needs—perceived insurance against external vulnerability—saw smaller output contractions. But this effect was pronounced only when reserves cover was low or moderate. For countries with ample reserves, having more reserves carried little additional benefit.

Avoiding excesses in the banking sector also helped. Countries that had domestic credit booms in the run up to the crisis tended to experience credit busts during the crisis; these busts were more pronounced in countries with fixed exchange rate regimes.

Response

Countries that entered the crisis with more policy space and less binding financing constraints were able to react with more aggressive fiscal and monetary stimuli. Those with lower public debt and better budget balances going into the crisis were able to accommodate the economic downturn better by letting their fiscal positions ease more substantially.

Similarly, those with lower pre-crisis inflation and sovereign spreads were able to cut interest rates more. There is also evidence that the exchange rate regime mattered—flexible regimes were able to provide greater monetary stimulus.

Recovery

There is evidence that countries that were able to increase public spending more rapidly have experienced faster recoveries, providing a concrete example of how better fundamentals—or more policy space—have helped. The positive role of the exchange rate as an adjustment mechanism is also becoming evident: countries with more flexible exchange rate regimes are recovering faster.

Exit

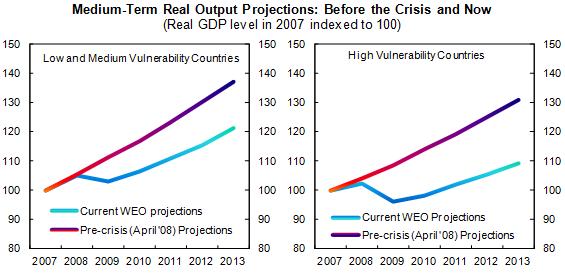

As emerging markets exit the crisis, they will need to tackle sharply different policy challenges. Those that entered the crisis with high vulnerabilities face larger output losses (relative to pre-crisis projections). If current account deficits persist, their external debt-to-GDP ratios could remain elevated.

Thus, this group of EMs will need to sustain adjustment over the medium term to bring vulnerabilities back down to more moderate levels.

On the other hand, those with better pre-crisis fundamentals are already facing a cyclical conundrum: while recovery in output and emerging inflation pressures would normally imply higher policy rates (in a Taylor rule framework), such actions in the face of continued accommodative policies in the advanced economies could prompt excessive capital inflows, possibly fueling asset price bubbles. This may be why many fast-recovering emerging markets are taking a cautious approach in withdrawing monetary stimulus.

Lessons

Fortunately, a crisis of this magnitude is a rare event. But the varied experience of emerging markets during this crisis underscores an important lesson: good policies beget good outcomes.

Investing during good times to develop a sound policy framework that delivers stronger fundamentals and lower vulnerabilities yields large dividends during crises. In the current crisis, low-vulnerability countries had lower output declines, more space to undertake countercyclical policies, and quicker recoveries.

Cross posted in the Huffington Post.